We sometimes teach our children things that we don’t intend. When I was a child we went to the beach often because Daytona was only about an hour away. My mother would routinely warn me about the undertow, you know, that current that pulls at your legs when you’re standing in the surf. It frightened me and one particular beach outing I was hesitant to go into the water. Try as she might, my mother couldn’t cajole me to join her even in the quiet surf. Finally, in exasperation, she said, “What’s wrong? Come in the water!” To which I replied, “No, I’m not getting in there with that big frog, the under toad!”

If only it were that harmless. What are we teaching our students? Let’s think about who they are. Every student at New Covenant is part of the iGeneration (iGen’s for short). Born between 1995 and 2013, they spend more time alone on an average day. Not surprisingly, nearly half report feeling left out of activities of friends, and they can see how left out they are because they can watch their friends live on their electronic devices. Nearly half of them report getting less than seven hours of sleep a night. Anxiety and depression are measurably higher with this group of children and the suicide rate for girls has doubled since 2007! iGenner’s are the first not to know the world without the internet, and they are the first to have grown up on smartphones, which they use an average of almost three hours a day.

We, their parents, are contributors to this, of course. Broadly speaking, we are politically polarized, so much so that our emotional commitment tempts us to hate or despise those of the other party. Many of us practice paranoid parenting, by which I mean we overprotect, overschedule, and over supervise. We do this because the 24/7 news cycle causes us to perceive the world is more dangerous than it actually is, while we know statistically that the everyday world of your child is actually far safer than when I grew up in the 60’s and 70’s.

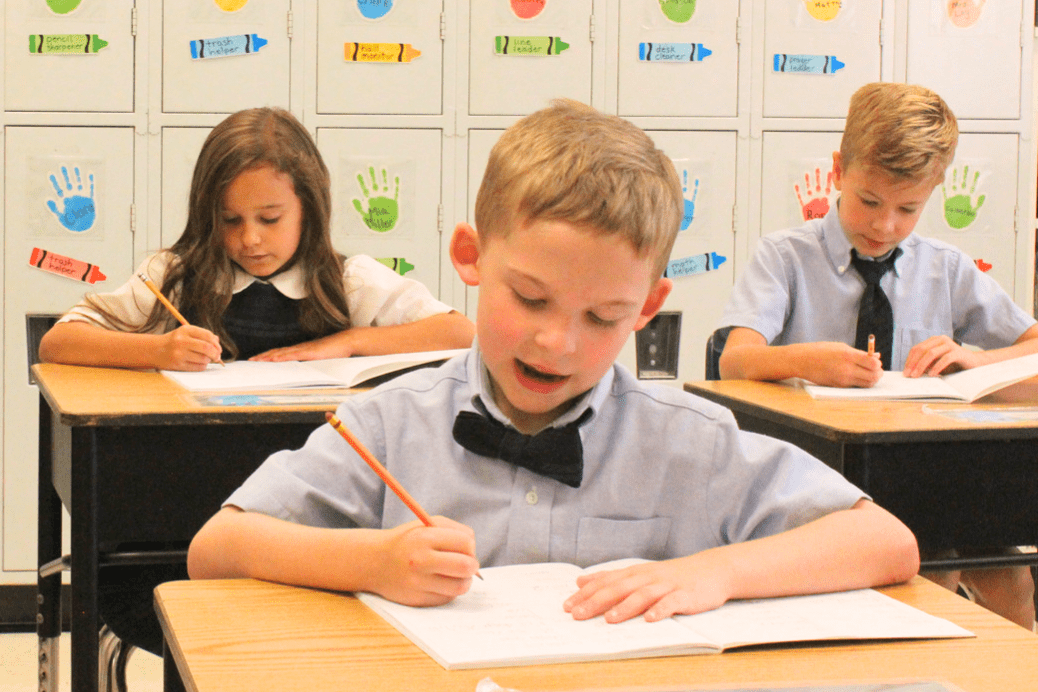

School age children today rarely have the experience of time to themselves, that is, time that is not scheduled and not supervised by adults. As a result, they’ve rarely had the free space to find something to play for its own sake. Over scheduling, over supervising and over protecting are now known to prevent children from learning autonomy, independence, conflict resolution, and social navigation.

According to the 2018 book, The Coddling of the American Mind, there are several untruths that we have taught our children. The first of these is the Untruth of Fragility: what doesn’t kill you makes you weaker. The lesson we’ve accepted is that children are fragile. Some things are fragile, like tea cups; some things are resilient, like plastic sippy cups for children; and some things are antifragile, meaning that they actually require stressors and challenges in order to learn, adapt, and grow. Systems that are anti-fragile become rigid, weak and inefficient when nothing challenges them or pushes them to respond vigorously.

Students actually need age appropriate stress and social conflict. They should not be emotionally protected from it. Grossly expanded conceptions of trauma and safety are now used to justify the overprotection of children of all ages, and there is an increasing obsession with eliminating all real and imagined threats to the point at which people will not make reasonable trade-offs that are demanded by practical or other moral concerns. This makes children more fragile.

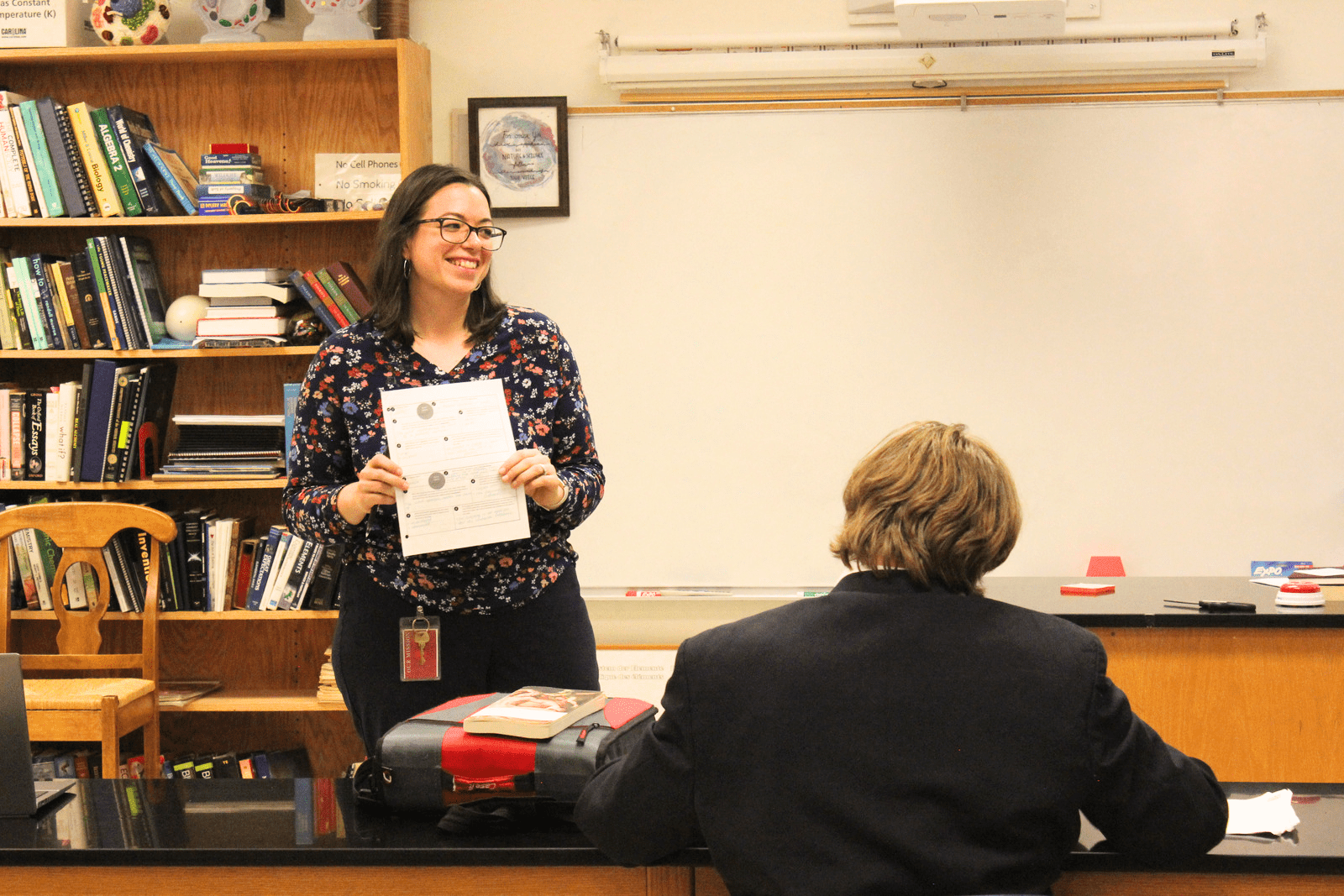

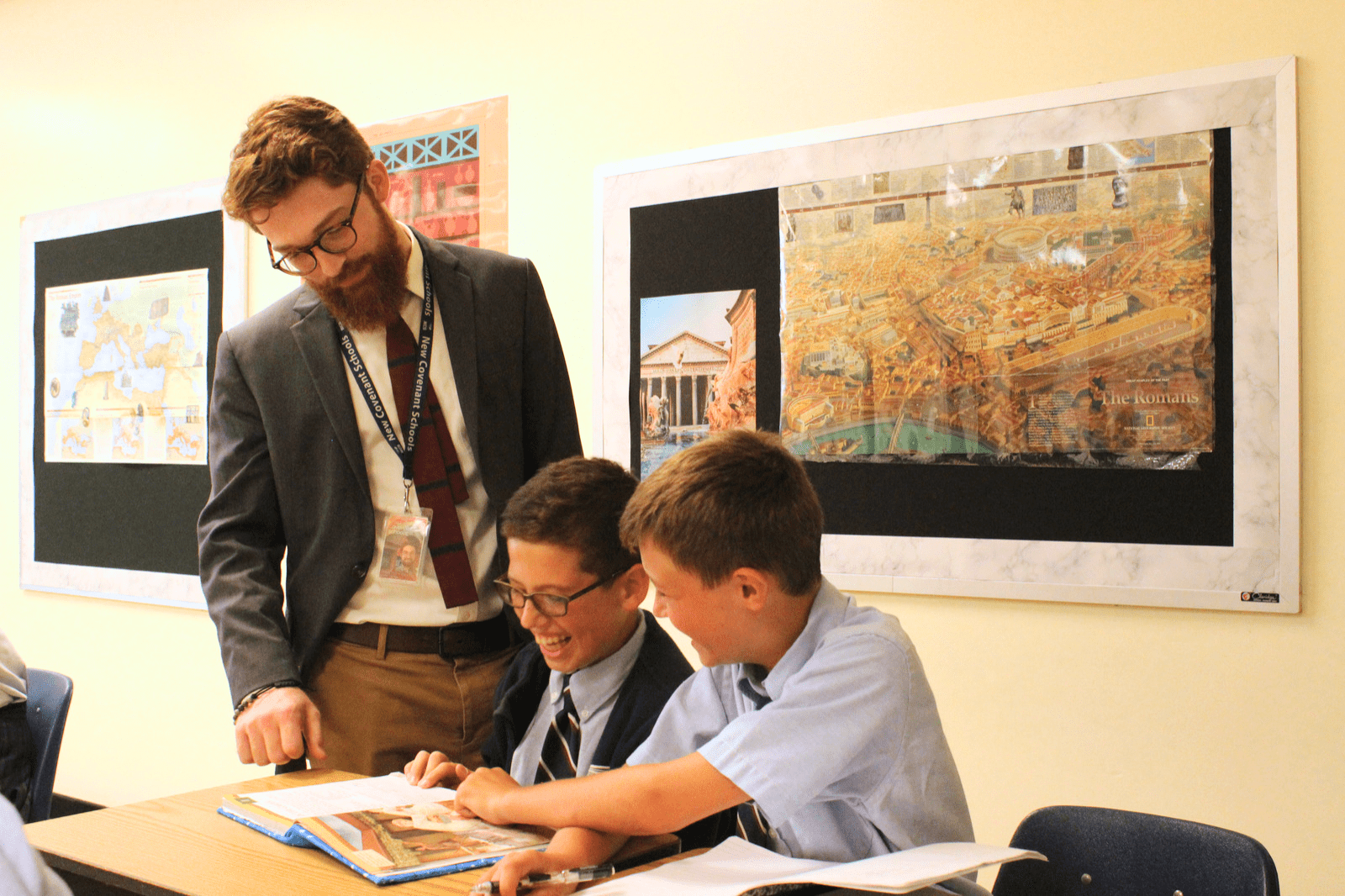

Childhood is the laboratory for learning to deal with distress, conflict and emotional difficulties. After all, as a child one’s peers are far less self-governed than they are as adults, and they can be cruel. In the classroom be assured that, at some point, with eighteen students in a class and 430 students across the school, someone’s child is going to hurt your child’s feelings, say something inappropriate, or do something mean. It will also happen when the teacher is either not present, distracted or unaware in some other way.

Our response to conflict and stress in our children’s lives is to help them find healthy ways to work through it. Seeking to protect students from all negative situations, both real and imagined, leads to what we call “safetyism” and is in full bloom on college campuses across the United States. Most of us watch students requiring safe spaces, stuffed animals, and freedom from any kind of “triggering” conflict, and struggle to understand their demands. The question we should think about is how are our parenting habits contributing to this kind of child development.

*Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. Penguin Press. New York, 2018