We live in a secular age. Charles Taylor, in his massive book which bears the above title, poses the question, “How is it that 500 years ago it was almost impossible not to believe in God, but now it almost impossible to believe in God?” In the older world and earlier Christendom, it was taken for granted that human flourishing – that is, our highest good – was completely predicated upon a divine transcendent, something outside of ourselves and infinitely or ineffably above ourselves. For Jews, that was Yahweh; for Christians that was Yahweh in the Messiah. Even for the pre-Christian philosopher, Plato, the transcendent was crucial to his whole metaphysic for particular iterations of transcendent forms. Today, however, we are faced with a view of man that admits of no final goals beyond human flourishing. In today’s secular world, any reference beyond ourselves is officially proscribed as essential to our common experience. Taylor explores three kinds of “secular,” in our culture.

Secularized public spaces.

This means that the welcome mat for religious ideas and expression is withdrawn, excluding them from public debate. This is most readily seen in the prohibition of Nativity scenes on courthouse property during Advent, but it extends deeper. For the secular mind, now imposed upon the culture, all religious thought and expression are relegated to private spaces. The effect is to make them irrelevant in public discourse. All appeals to public morality and public policy fail if they are religiously grounded. If all religion is merely private, then no one is bothered if you say “Jesus is Lord,” so long as we all agree that he is only Lord of some private space in your life. We are no longer welcome to affirm that “Jesus is Lord” in the way early Christians provoked Caesar to throw them to the lions, that is by asserting that Christ’s claims on all life are comprehensive.

Personal Secularization.

The second kind of secularism is the decline in belief and practices in families and children. Increasingly, we are untethered from traditional religious affiliations and from the practices of piety that are associated with and reinforced by them. This can be tracked by declining church attendance, and in the personal religious habits of our students. By today’s statistics 75% of Christian young people express their disinterest in faith by dropping out of it altogether in their college years. It is no longer relevant to them.

Secularized belief.

Taylor suggests that the third kind of secularism is new. For the first time in history, Western culture has undergone a change in what it sees as conditions for belief, the exclusion of the transcendent as a necessary condition for human flourishing. He calls this the “immanent frame,” by which he means that the privatization of belief is so thorough-going that, as a people, we no longer look for meaning outside of the framework of our empirical experience.

The older Christian belief has been rendered irrelevant and completely privatized. The thorough-going secular spirit is no longer limited to philosophers, artists, and cultural elites. It is the coin of the realm and everyone trusts the currency. It has saturated the culture in literature, movies, politics, and especially science. It is now assumed as much as a divine transcendent was once assumed, which explains why religious belief is nearly impossible. This is a functional atheism in which students no longer look outside themselves for a reference point of meaning. Faith no longer has any contact with reason.

The results of this change are challenging. First, students have little sense of religious authority. What is left of organized faith caters so profoundly to the individual, that it reinforces the secular claim that religion is intensely and only personal. No wonder that religious activity is consumer driven.

Second, students have a growing sense of equality of opinion on most matters. There is a tendency to flatten out the differences between teacher and student. Truth is held to be a matter of opinion with a relative and situational quality about it, rendering one opinion equally valid as another.

Third, students have a low concept of the place of the Scriptures in the life of believers beyond personal devotional practices. If there is no meaningful transcendent, the Scripture itself no longer occupies the authoritative space it was once acknowledged to have.

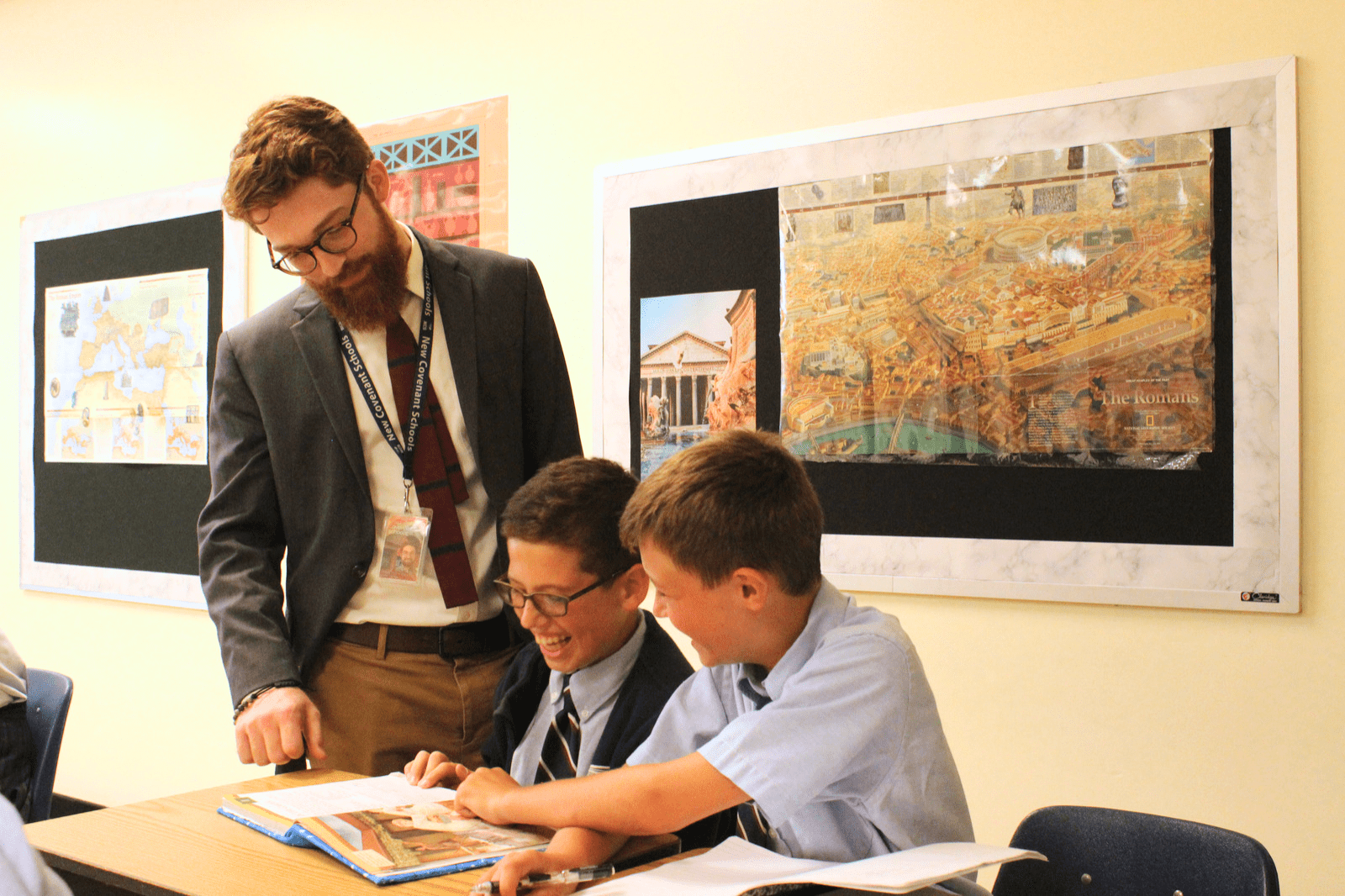

Classical, Christian education cuts powerfully against this secular grain. It presupposes that our highest good is to glorify God and enjoy him forever. It holds a high view of the Scriptures which give us the rule by which we can love and obey him. For classical, Christian education, faith is not a private matter; it is a central presupposition that makes learning about God’s world possible and intelligible.