Could the magi have seen what the shepherds saw on the same night?

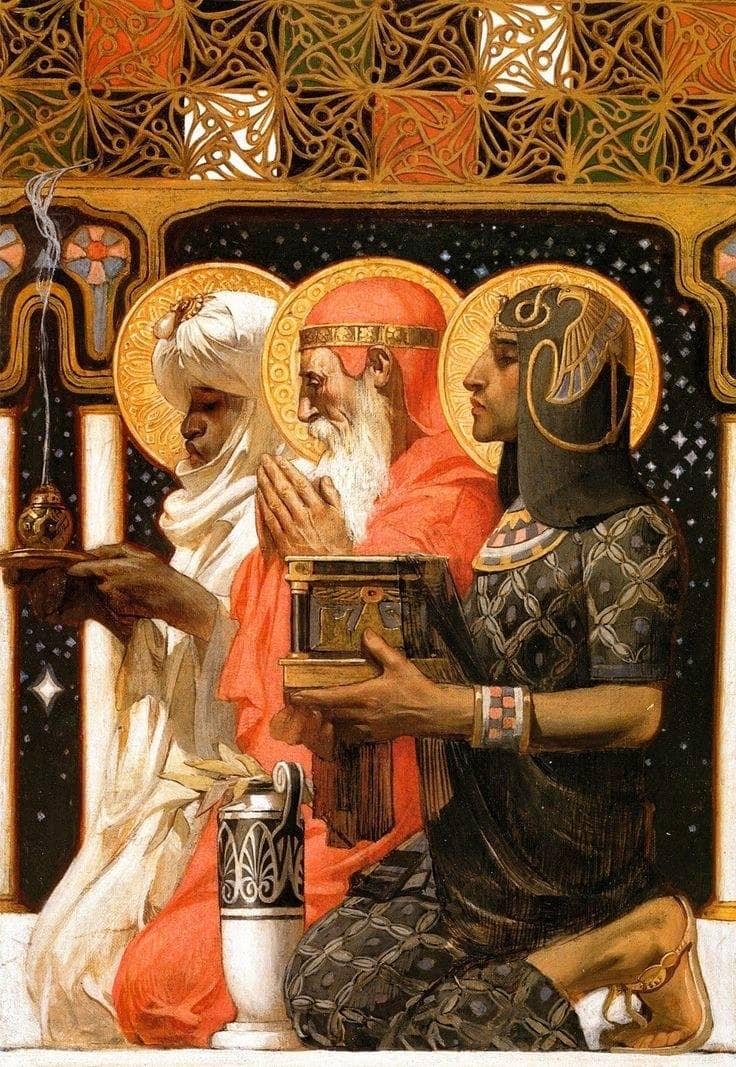

It’s a fascinating story we know well. No story in the Bible has been subjected to more speculation or more romance than the story of the three wise men. Anglicans are no exception. In our own hymnal, the carol “We Three Kings,” not only affirms the number of Kings at three, but goes so far as to appoint solos for choir members labeling each solo with the name of one of the three visitors: Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazar!

In the days of Herod the King, MAGOI came from Anatolia, away to the east. This word comes into English as “magicians” and they are part of a long tradition of councilors to pagan kings – not kings themselves – but maintained in royal courts as advisors and astrological omen readers. Let’s call it Bagdad – we don’t know – but the trip to Jerusalem is about the distance from Lynchburg to Memphis, depending upon the point of origin and the route. The caravan routes in the ancient world are well-known.

It was in the days of Herod the King, this would have been “the Great,” and a perusing of the historical record offered by Josephus, a first century writer, reveals him to be a monster. He was likely psychotic, serially murdered his wives and ruled despotically. He was spectacularly cruel, and nobody liked him, but he had the backing of Rome and was invulnerable to political coup. He was not Jewish – the Herodian line were Edomites, originally descended from Esau, not Jacob. The Romans put him in power as a strong man. Rome had tensions with Persians on their Easter boarder, and conflicts that erupted between the two powers usually did so in or around the Judean neighborhood, making Israel something of a buffer state.

When a large entourage of Persians clattered into the dusty streets of Jerusalem, it was front page news. There were the “wise men,” yes, but there were likely cohorts of soldiers, cooks, baggage handlers, and the like, everything you would expect a caravan to have, when traveling cross country in the ancient world.

Their inquiry was simple: Where is he that born king of the Jews? The irony of Matthew is pretty thick. No one seems to know or to be aware that a king has been born. But if such had been born it would not be welcome news to Herod. When Herod was troubled, all Jerusalem was troubled. When Herod was troubled, heads always rolled. The word used here means “agitated,” but the noun form of the word is nearly identical to the verb form used here, and means “tumult, sedition, or insurrection.” It’s likely a play on words to convey more than anxiety; it points clearly to a possible challenge to the established powers.

The magi also mention that they had seen “his star while they were in the east…” Here is the where speculation has gone pretty far. I’ll admit that we don’t know; the text doesn’t say. Johaness Kepler suggested that a confluence of two planets in the constellation Pices in 7 BC probably created a bright light enough to attract the attention of astrologers. Some argue that it was a comet and recreated the appearances of several candidates. None of these really satisfy what the text does say – that at a certain point the star, which they had seen appeared to them and led them over the place where the young child was. Comets and confluences don’t do this.

If I had to guess – and I am speculating – here’s what I think happened. If we rewind the clock to the night of Jesus birth, we know that angels appeared to the shepherds, the Luke is clear that the “glory of the Lord shone round about them.” This was the glory of God, the visible and glorious presence of God that as a “pillar of fire by night” led the children of Israel out of Egypt, through the wilderness and inhabited the tabernacle and later the temple.

We know from Ezekiel 8-10 that this glory of God removed itself from the temple, which had been polluted by idolatrous priests, and Ezekiel saw it migrate East to Babylon where God took up resident with his people in exile, disobedient though they were. There is no record that Yahweh ever came back. Seventy years later, the people began returning, they rebuilt the temple, but that glory presence never returned. Yahweh gave no visible sign that he had followed them home. The exile really wasn’t over. Until that great night. The shepherds saw the glory of God. It was back. God had visited them.

That same night, 600 miles away there were some Zoroastrian astrologers watching the sky. What were they doing? They were expecting something. They were expecting the birth of Messiah the Prince. This is not speculation. One of those Jewish exiles living in their region had quite a bit of exchange with the magicians of the court of his day. His name was Daniel, and he was only five centuries removed from the wise men of our story. They knew who he was. It is no more of a stretch to believe that, any more than it is a stretch for us to be familiar with the writings of, say, Martin Luther who is removed from us by the same amount of time. Daniel was famous and well-known. He was the dominant personality in Babylon for nearly a century, being exiled as a young man in the first wave of deportation, and having lived through the reigns of five different kings, and the decree to return to the homeland.

Daniel didn’t speak of a star, but he left behind a clock. He said that, from the issuing of the decree to return until Messiah the Prince would be 490 years. That edict was published between 535 and 480 BC depending upon which dating you use; but at any rate the clock started ticking. By the time we get to the first century, at least in religious and political circles, messianic expectation was palpable. Our wise men sat, night after night, probably reading Daniel, adjusting their calculations, and watching the night skies for astrological omens.

If I had to guess, the night of Jesus birth, they saw the backside of the glory of God revealed to our shepherds. They immediately began packing. And on they came. The first Gentiles were coming to the light of the Christ.