It’s endearing and amazing to see five-year olds reciting the Timeline, but the magic of this learning tool doesn’t fully reveal itself until our students become our graduates. If you’re new to New Covenant, you might not know about this piece of our curriculum.

The seed for the idea came years ago from our reading of Dorothy L. Sayers’ essay, The Lost Tools of Learning, in which she advocated strongly for the traditional method of education which included memorization for younger children. Most of our parents are young enough to have come through progressive schools where memorization was frowned upon. Indeed, some critics of New Covenant disagree with us most firmly on this point—that is, they believe that children should not be required to memorize much of anything! The underlying assumption is that rote memory is not meaningful, and therefore, unhelpful.

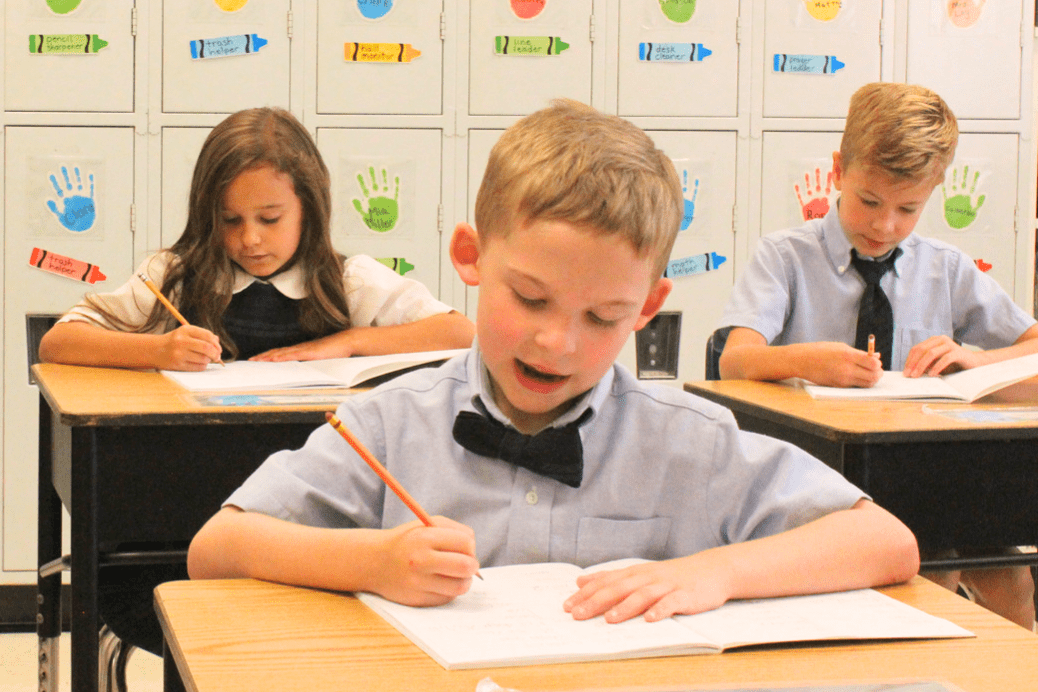

We disagree. In the essay Sayers reminded us that in the classical tradition “recitation aloud should be practiced, individually or in chorus; for we must not forget that we are laying the groundwork for disputation (logic) and rhetoric.” She went on to point out that since children have an enormous capacity to memorize at a time when it is neither burdensome nor onerous, we should take full advantage. We ought to fill their minds with all kinds of things—math facts, geographical facts, and, of course Latin paradigms. The Latin conjugation, amo, amas, amat, (I love, you love, he/she/it loves) is no different to a child than eeney, meeny, miney, mo.

But what is the purpose of the history timeline? Sayers addresses it perfectly:

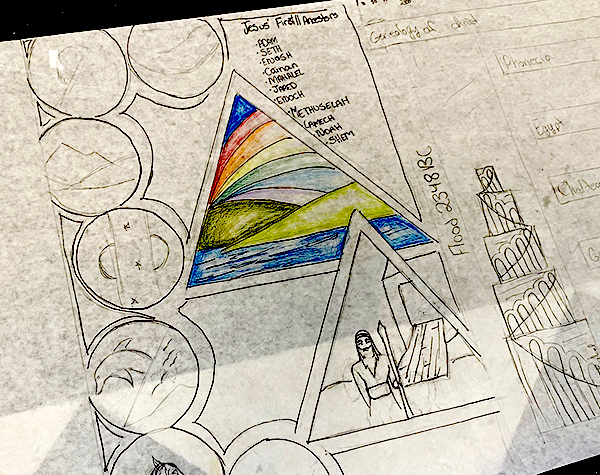

“The grammar of history should consist, I think, of dates, events, anecdotes, and personalities. A set of dates to which one can peg all later historical knowledge is of enormous help later on in establishing the perspective of history. It does not greatly matter which dates: those of the Kings of England will do very nicely, [she was British, after all!] provided that they are accompanied by pictures of costumes, architecture, and other everyday things, so that the mere mention of a date calls up a very strong visual presentment of the whole period.”

Beginning in kindergarten our students learn our own history timeline. It consists of 91 dates that we chose—events from each century of recorded human history. Over time the events and dates teach students that history is linear, and they provide pegs in students’ minds upon which they might hang information later in their education. The youngest children use hand motions to help them remember each date in sequence. In addition, we have provided our teachers with a visual media program that illustrates each event in the timeline so that they can drill with the slides, or simply display the slide when they are addressing the event more thoroughly in the later grades.

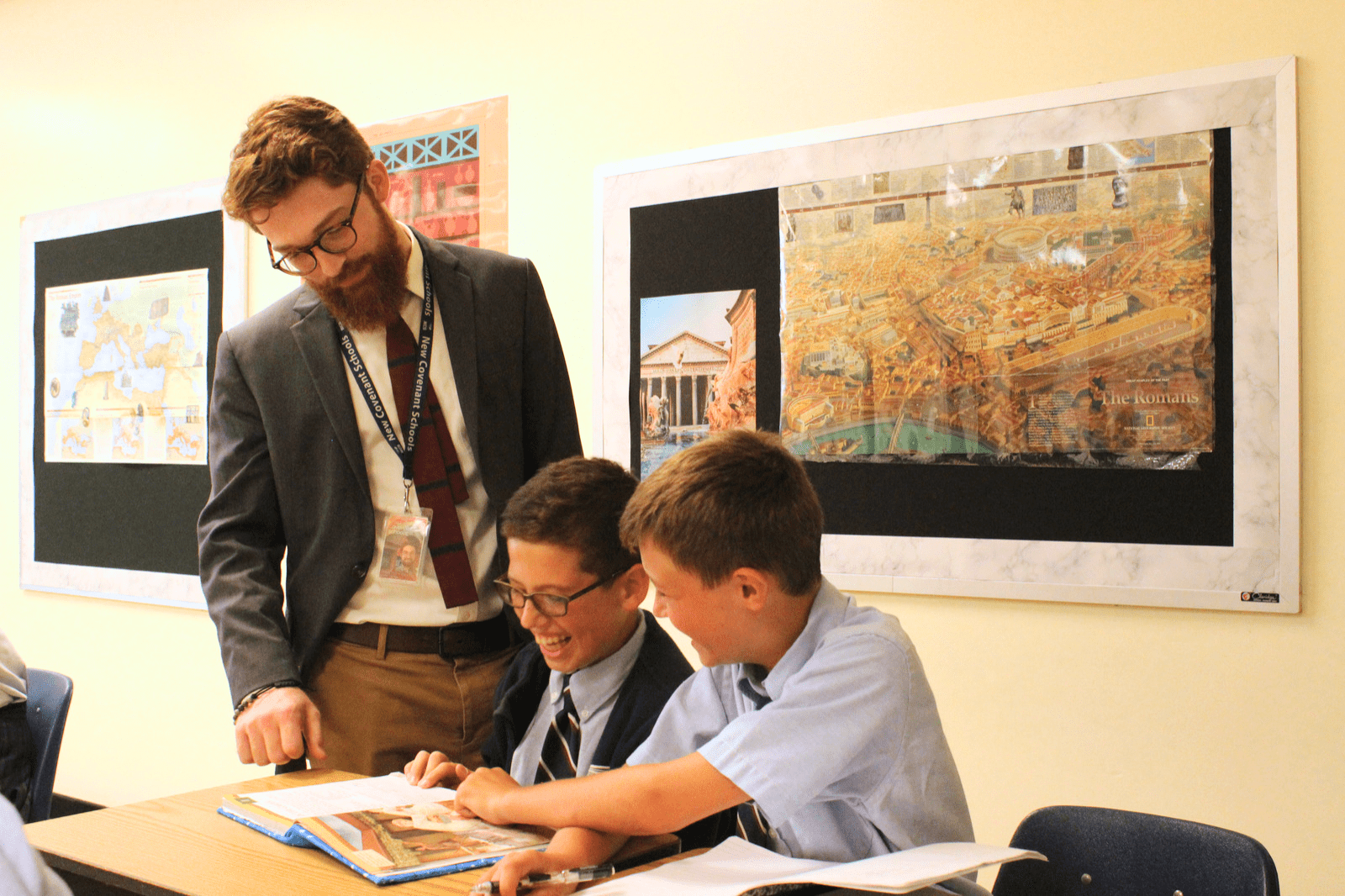

It takes a long time to travel through it. As students progress through the grades, this timeline is entrenched in their minds. One graduate remarked, “It’s something you wish you could forget, but you just can’t! It’s been drilled into me.” It provides an outline—I call them pegs—that students can use mentally to locate themselves in history. By the time they reach 10th grade they will re-create timelines of the world in world history class. You can see the ten-foot scrolls they are making right now in the School of Rhetoric wing!

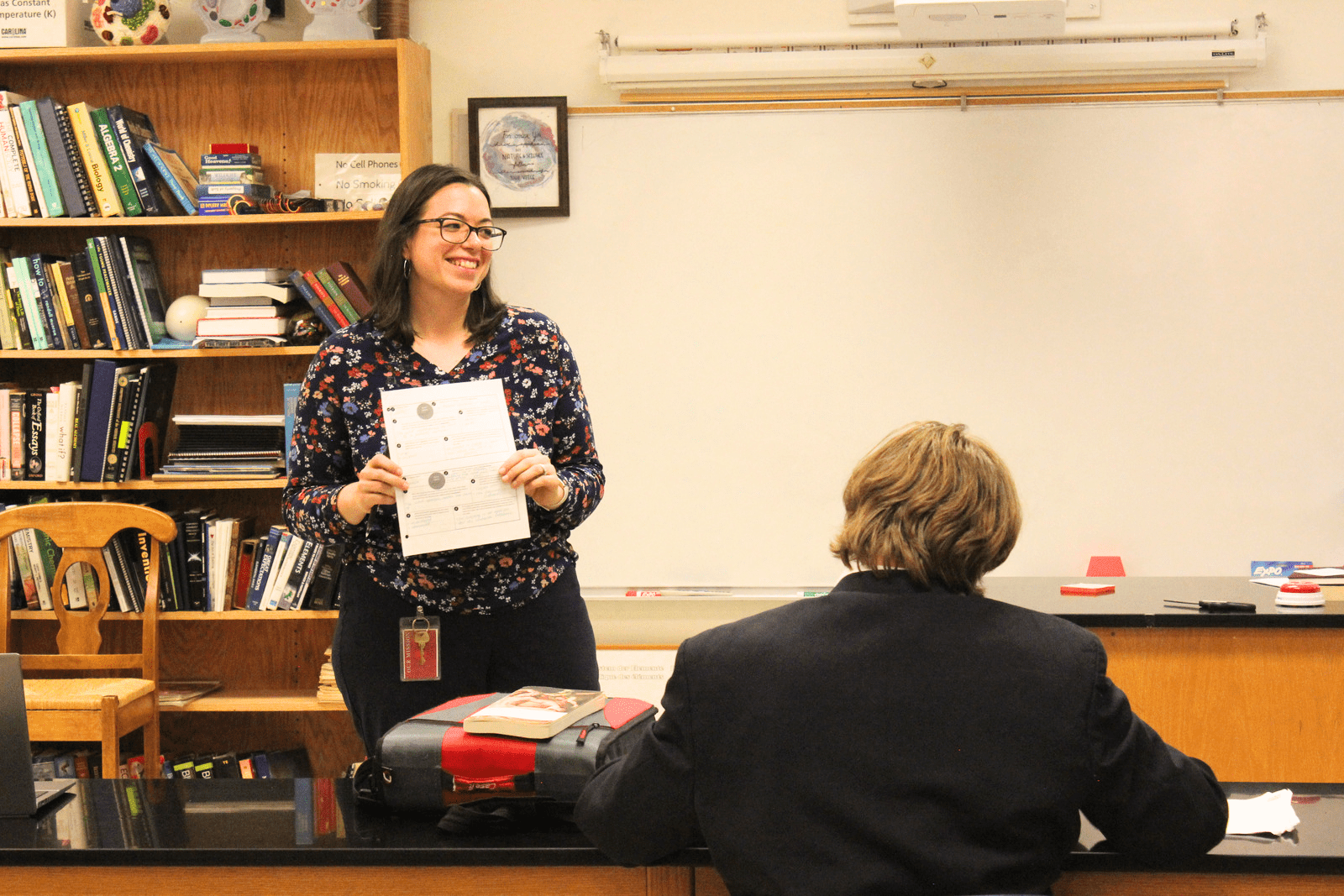

Built upon this foundational knowledge, there is a higher level. I teach our seniors in Intermediate Greek. Most were here in grammar or middle school. Because of the History Timeline, all of them know that the Council of Nicea was held in a.d. 325. They learned it as youngsters, and again in world history, along with the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, Constantine and the fall of the Roman Empire. By the time they reach me, they are ready for a capstone assignment. Each year my students translate the Nicene Creed from Greek to English, the exact creed produced by bishops from around the Empire at the Council in a.d. 325. This is the same creed recited each week in traditional churches, and is recognized by the Church as the very definition of what a Christian must believe.

Moreover, we spend a week discussing its history and significance. I show them how the Council of Nicea has impacted their lives more than the Vietnam War. As we know, the Creed of Nicea declared that the only man in the history of the world to possess deity was Jesus the Christ. The political implications for Constantine meant that the door was forever closed to all those who would rule and reign as gods on earth, as had the recent Roman Emperors, and as Constantine might secretly have wished to do. The Council of Nicea provided the deep rationale for denying the deity of emperors, transferring it properly to the King of Kings. The Christian West was born in a.d. 325, and in one stroke it provided the intellectual preconditions for individual liberty and the restraint of totalitarian governments that had dominated the ancient world. In short, it made possible the republican form of government we enjoy in America today.

Do our kindergarteners know that? Of course not. Do our graduates? If we do our jobs, they should. It all begins with the History Timeline.