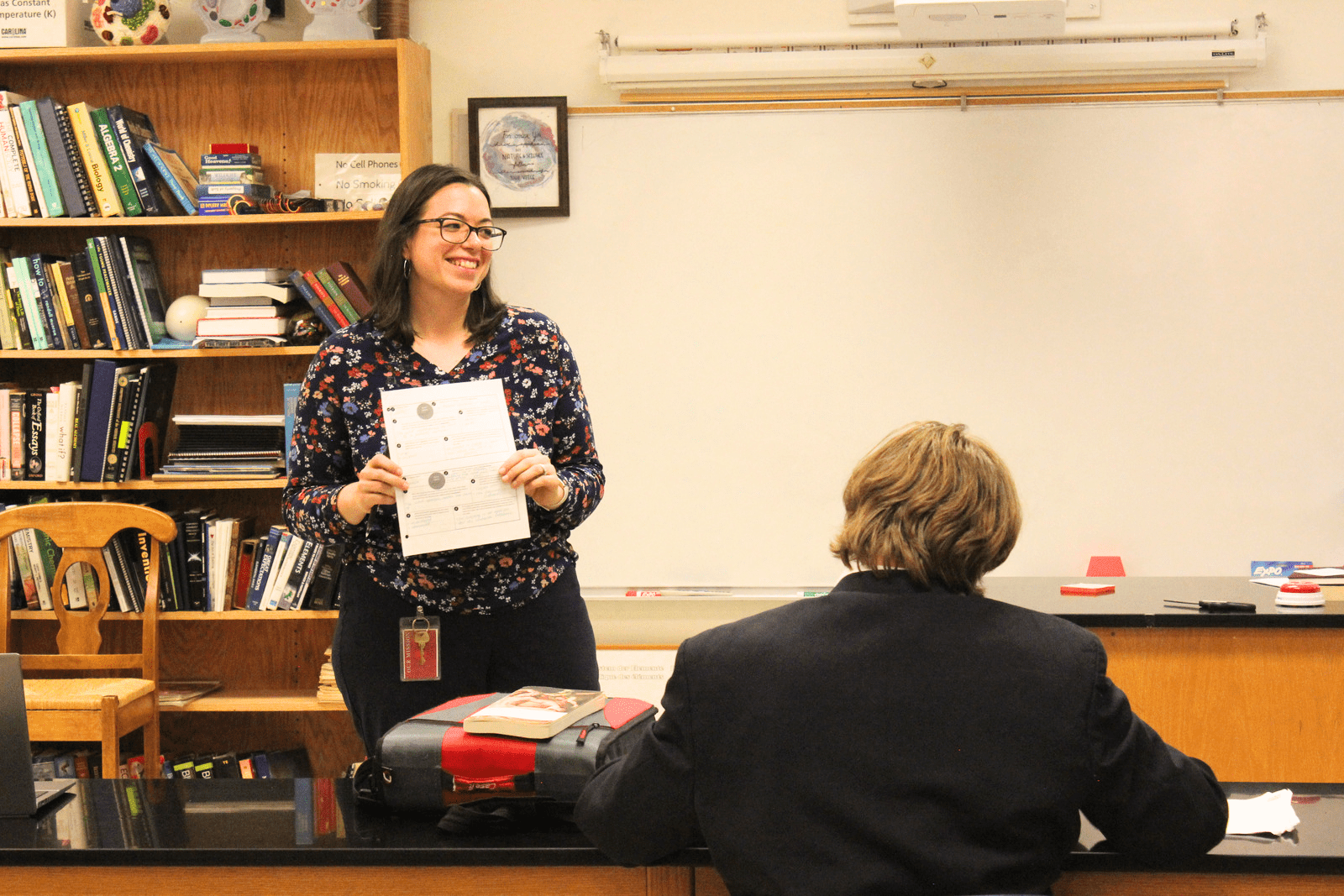

New Covenant administrative staff continuously reviews the place of technology in our pedagogy and curriculum. In recent years we have surveyed our graduates in college who have given very specific feedback on the computer skills they felt they needed to make the transition to the collegiate setting. This resulted in the development of specific objectives that are now embedded across the curriculum in the School of Rhetoric, with more on the way.

Nevertheless, current research continues to support our posture that overuse of computers in the classroom – technology for its own sake – does not result in better learning, at least as measured by standardized tests. In short, the presence of technology is not an unqualified good.

Writing in June, 2019, for the online journal The Pacific Standard here, Tom Jacobs has called attention to a major new study from the Reboot Foundation. The study analyzed data from two sources: the 2017 National Assessment of Educational Progress, which provided math and reading scores for American fourth and eighth graders; and the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) which provided data from 30 nations suggests that, while computers can sometimes help children grasp certain concepts, their overuse is highly worrisome.

The research controlled for various factors that could affect student achievement, including household income, teacher training on the use of computers in education, and, for the international students, the size of the nation’s economy. The data identified several disturbing trends. Across most countries, a low to moderate use of school technology was generally associated with better performance – relative to students reporting no computer use at all.

Moderate Computer Use Correlates Positively

Helen Lee Bouygues, President of the foundation says that “when students report having access to classroom computers and using these devices on an infrequent basis, they show better performance,” but when students report using these devices every day, and for several hours during the school day, performance lowers dramatically.” American fourth grade students who reported using laptops or desktop computers in more than half or all of their classes scored 10 points higher than students who reported never using those devices in class. Likewise, students in France who reported using the internet at school for a few minutes to a half-hour every day scored 13 points higher on the PISA reading assessment than students who reported spending no time on the internet at school.

Extensive or exclusive Computer Use Correlates Negatively

Those students who were online in school for more than 30 minutes per day consistently scored lower than their peers on the same test. Students who reported a high use of school technology trailed behind peers who reported moderate use.

Now for the bombshell: The results regarding tablet use in fourth grade were particularly worrisome. American fourth grade students who reported using tablets in all or almost all classes scored 14 points lower on the reading exam than students who reported never using classroom tablets. This difference in scores is equivalent to a full grade level, or a year’s worth of teaching (emphasis mine).

The findings of this latest research is consistent with two earlier major studies, Angrist and Lavy, 2002 and Fuchs and Woesmann, 2004, which relied upon similar data as the Reboot Foundation. I discuss both of these extensively in my 2015 master’s thesis, Education in Context of Student-accessed, Digital and Applied Technology, which you can find on our website under the tab Glad You Asked/Technology, or just click here, .

These results do not prove causation, of course, but they are certainly cautionary. The overuse of computers correlates with diminishing and ultimately counterproductive, results. New Covenant is committed to appropriate instruction in computer technology and to the appropriate deployment of technology in the classroom. The current data, however, continue to suggest that chasing tech without caution is not a sound educational practice.