I consistently tell prospective parents that there are a hundred ways to teach students how to read. There are also some ways not to teach them. Reading is not a natural function of the brain. Humans didn’t invent an alphabet until 3200 BC, or thereabouts, and reading by the masses, as opposed to professional scribes, is a relatively recent phenomenon.

We know how to teach children to read. Symbols represent sounds and combinations of symbols represent combinations of sounds. There are rules that govern the order and function of the symbols, and in English, it’s quite a complex code. There are seventy two sounds in the English language, all of which are represented by what linguist Romalda Spalding called phonograms. Intensive instruction in these phonograms will virtually ensure that a young child will learn to read. In addition to the sounds themselves, there are twenty-nine spelling rules in the English language, which, if mastered, will give understanding of how to spell in general, allowing students to avoid having to learn to spell every new word as it comes along. Over the history of New Covenant, it has been our joy to see nearly all our children succeed in this curriculum.

This is not hard. We’ve known how to teach children to read for centuries. That is why I find the recent article from American Public Radio, Why Millions of Kids Can’t Read, And What Better Teaching Can Do About It (available here) so infuriating. Yes. That’s not too strong of a word; the situation is inexcuseable.

The story profiles Jack Silva, the chief academic officer (emphasis mine) for Bethlehem, PA public schools. He noticed that nearly half of his third graders did not have reading proficiency and he wanted to know why. His staff wanted to blame poverty – the usual suspect – for the scores, but that was problematic because his district had swaths of affluence, and the scores were equally bad in rich schools.

It didn’t take long to find the real culprit. Most of the teachers in his district were taught by “reading professionals” to believe that “the most important thing was for the child to understand the meaning of the story, not the exact words on the page. So, if a kid came to the word “horse” and said “house,” the teacher would say, that’s wrong. But… “if the kid said ‘pony,’ it’d be right because pony and horse mean the same thing.” Jack Silva was shocked.

You should be as shocked as he was. NPR makes this astonishing admission: “This advice to a beginning reader is based on an influential theory about reading that basically says people use things like context and visual clues to read words. The theory assumes learning to read is a natural process and that with enough exposure to text, kids will figure out how words work. Yet scientists from around the world have done thousands of studies on how people learn to read and have concluded that this theory is wrong.”

It would be alarming if this was limited to the Bethlehem public school system. Sadly, it is not, as NPR further admits: “Across the country, millions of kids are struggling. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, 32% of fourth-graders and 24% of eighth-graders aren’t reading at a basic level. Fewer than 40% are proficient or advanced.”

So what did Bethlehem school district do? They spent more money, of course – $3,000,000 to be exact. What for? To teach their teachers how to teach reading phonetically. The program they chose wasn’t Spalding’s, but at least it was a commitment to reading by phonics, a self-evident solution. One teacher who attended the training, feeling betrayed by her expensive education said, “Why wasn’t I taught this?…What about all the kids I’ve been teaching all these years?”

For years New Covenant has been winked at by professional educators who have held phonics instruction to be quaint, outdated, and unnecessary. Their dismissiveness of centuries of pedagogy is breathtaking. Sure, some children are able to build their own knowledge of the relationship of symbols to sounds by using linguistic cues, context and pictures. Such methods, however, leave nearly half of our children behind. The only foolproof method for learning to read a phonetic language is a phonetic approach.

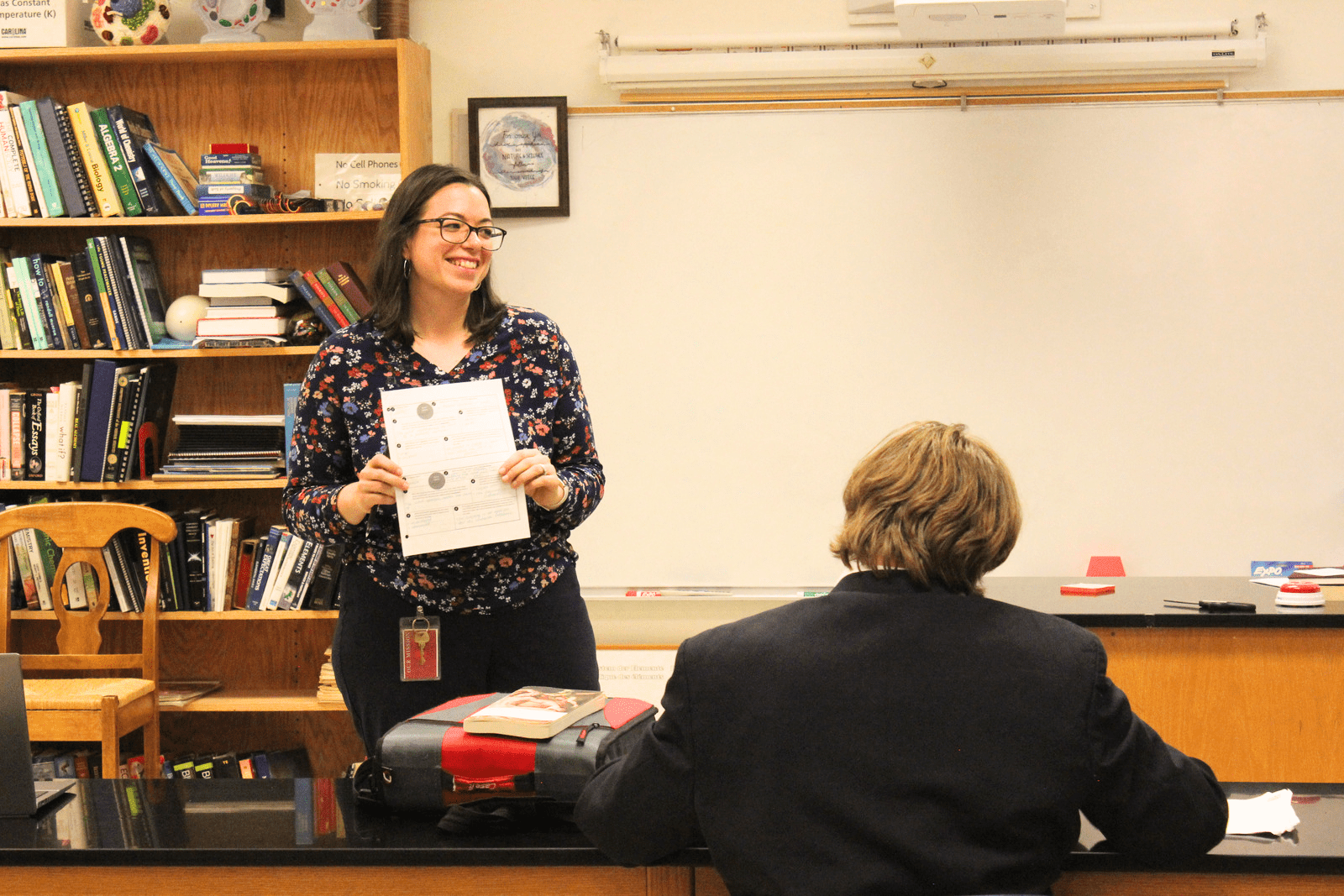

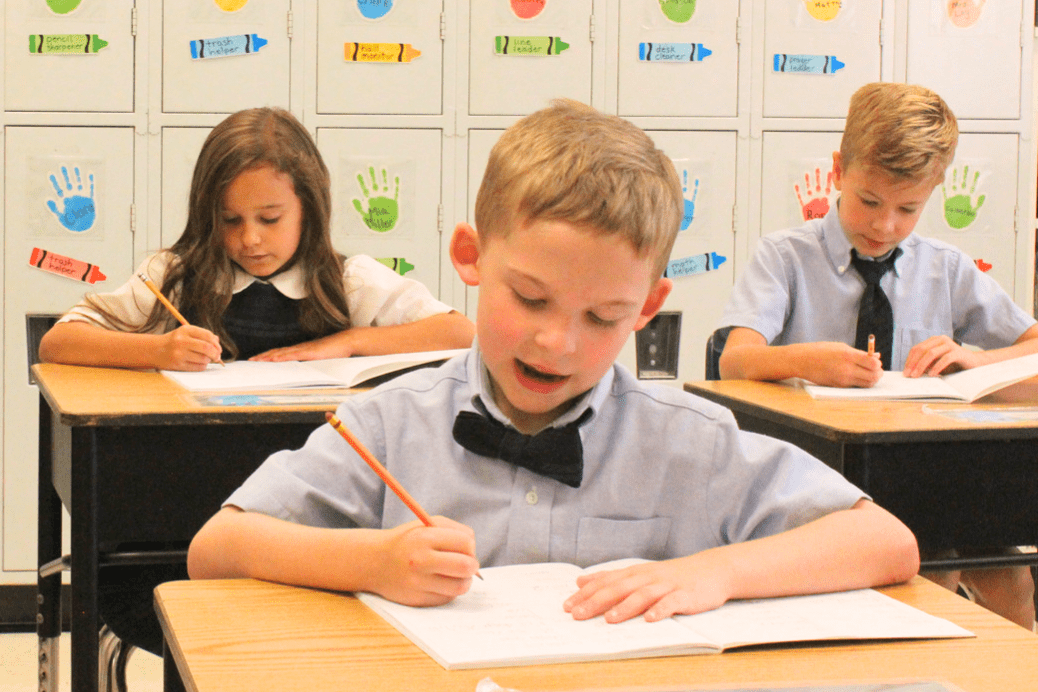

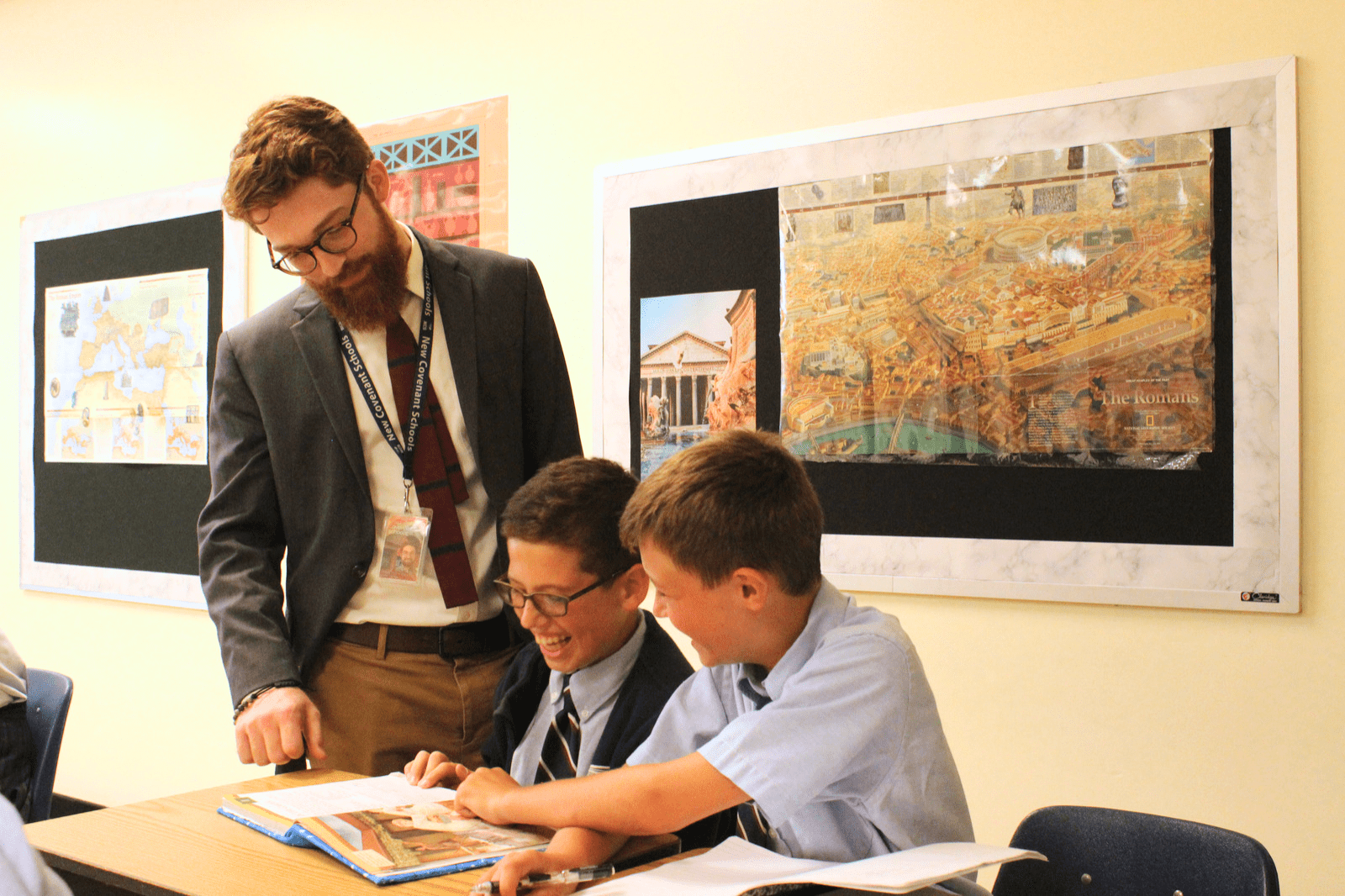

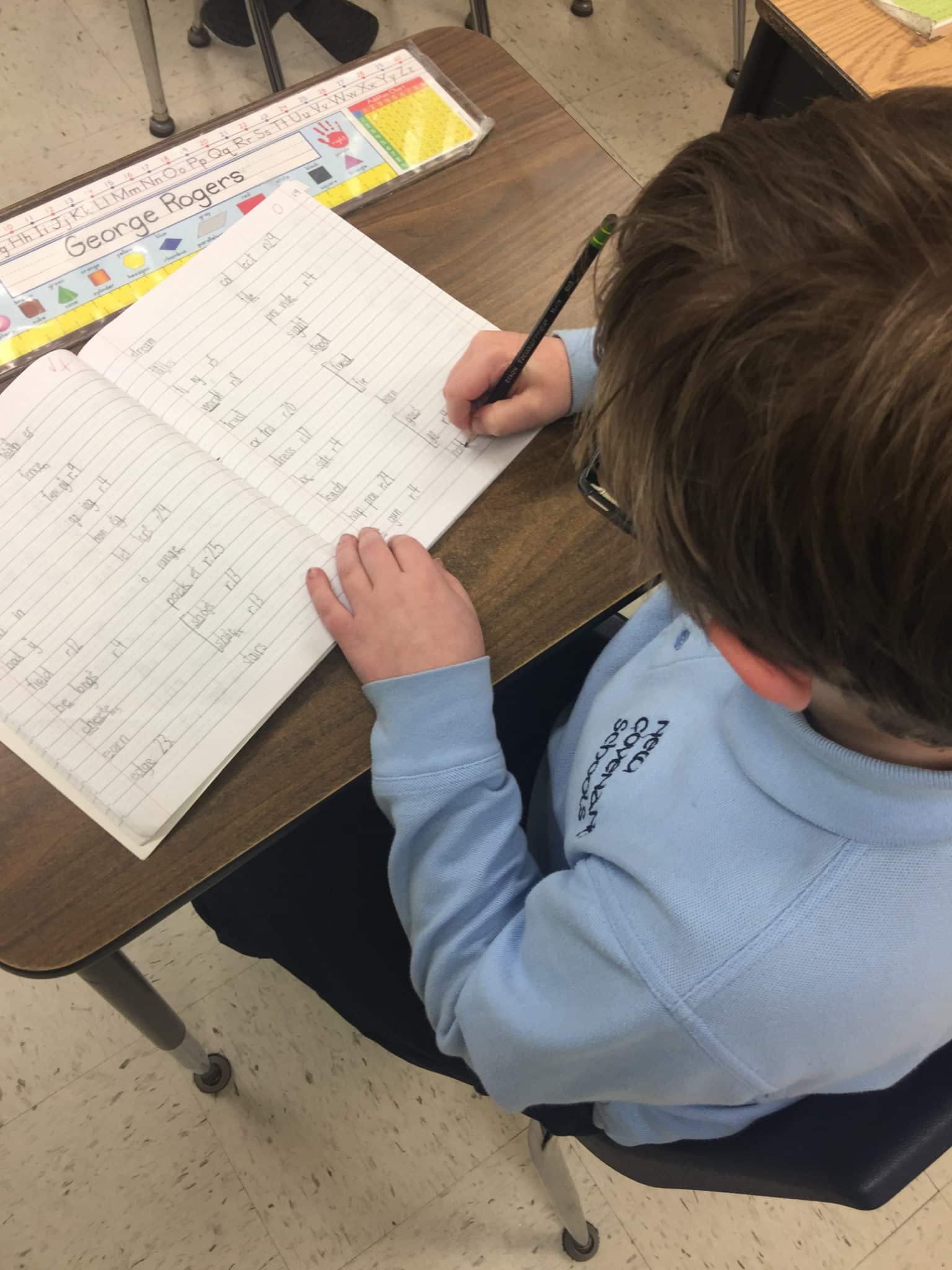

New Covenant uses Romalda Spalding’s Method, also known as The Writing Road to Reading. Central to this method is the mastery of phonograms, and it is accomplished by an educationally sound and important sequence of teaching. In a typical session in grades K-4, our students hear the word pronounced, noting the syllables of the word, as the teacher holds up her fingers to indicate each syllable break. She also notes one, two, and multi-letter phonograms. Students repeat the word phonetically and vocalize it again as they write it into their composition books. They underline the phonograms, and use numbers to signify the first, second, or third sound a letter might by making. Then they write the number of the rule that governs the spelling.

All this looks tedious to an adult who witnesses it for the first time. Young children, however, become engrossed in the challenge – there is a lot going on in their brains and bodies during a typical Spalding lesson! By the end of kindergarten, children are “reading ready,” and by about November of the first grade year, they are able to read from real books – not strictly controlled readers which only include words they’ve memorized. Seeing this miracle happen is amazing. Don’t be fooled. A grammar school that does not take words seriously in a phonetic way is putting reading at risk.