One of the most important questions we could ask of any curriculum is this: “Does the curriculum cohere?” To put it a different way, we’re asking if the curriculum progresses in developmentally appropriate ways, if the curriculum moves at an appropriate pace, if its methods are consistent with the content explored, and if it addresses core knowledge. Most importantly, we are searching for its  organizing principles.

organizing principles.

In short, a curriculum must hang together. A classical, Christian curriculum does so in two ways. First, our curriculum is informed by the Trivium: grammar, dialectic and rhetoric. These are not disciplines of study per se; rather, they are modes of learning, ways of approaching subject matter.

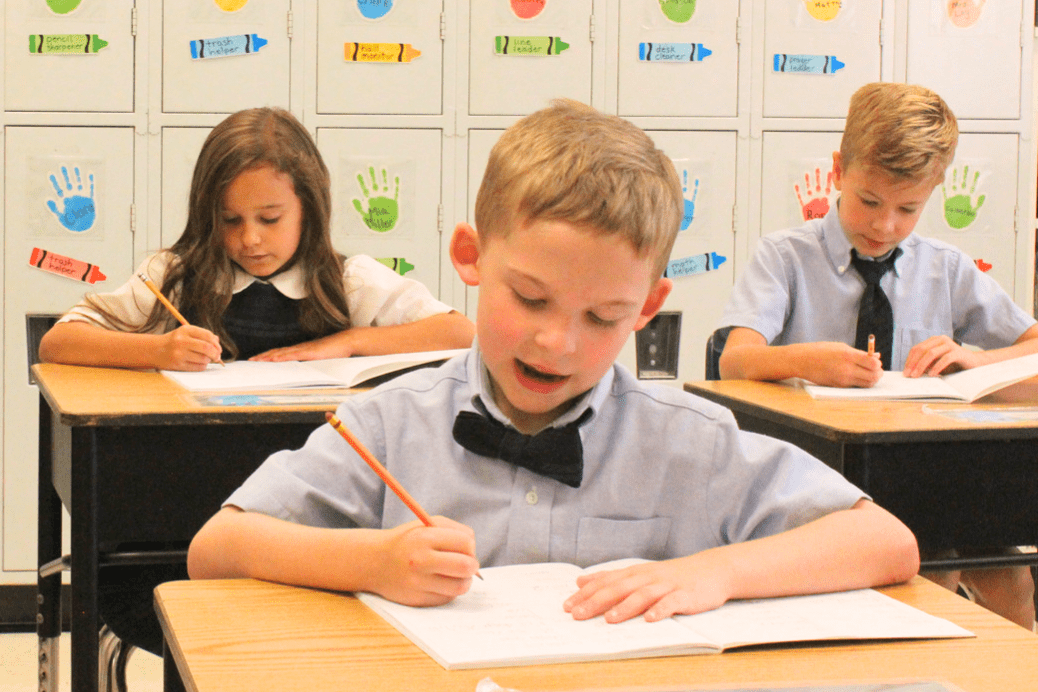

Everyone knows what we mean by English or Latin grammar, the basic parts of language governed by rules with internal logic. Similarly, we can speak of art, music or math, each having its own grammar. The chief concern of grammar school is discovery, the acquisition and mastery of facts and skills.

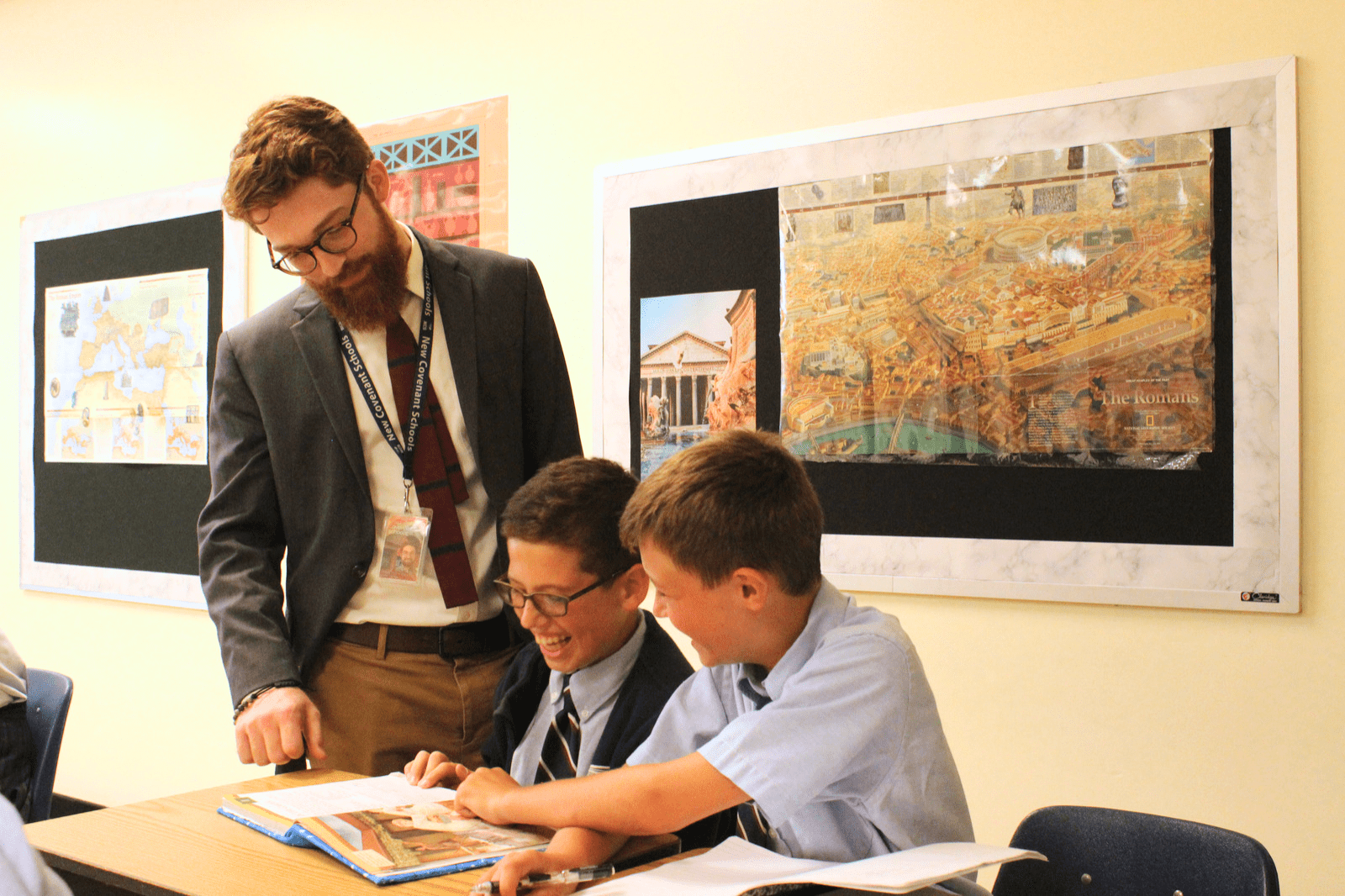

As a mode of learning, dialectic is concerned with understanding relationships, causes, results, and implications. A dialectic student is taught to question, to ask why, and to provide and evaluate evidence for opinions. Dialectic is the use of logic in order to analyze and synthesize facts.

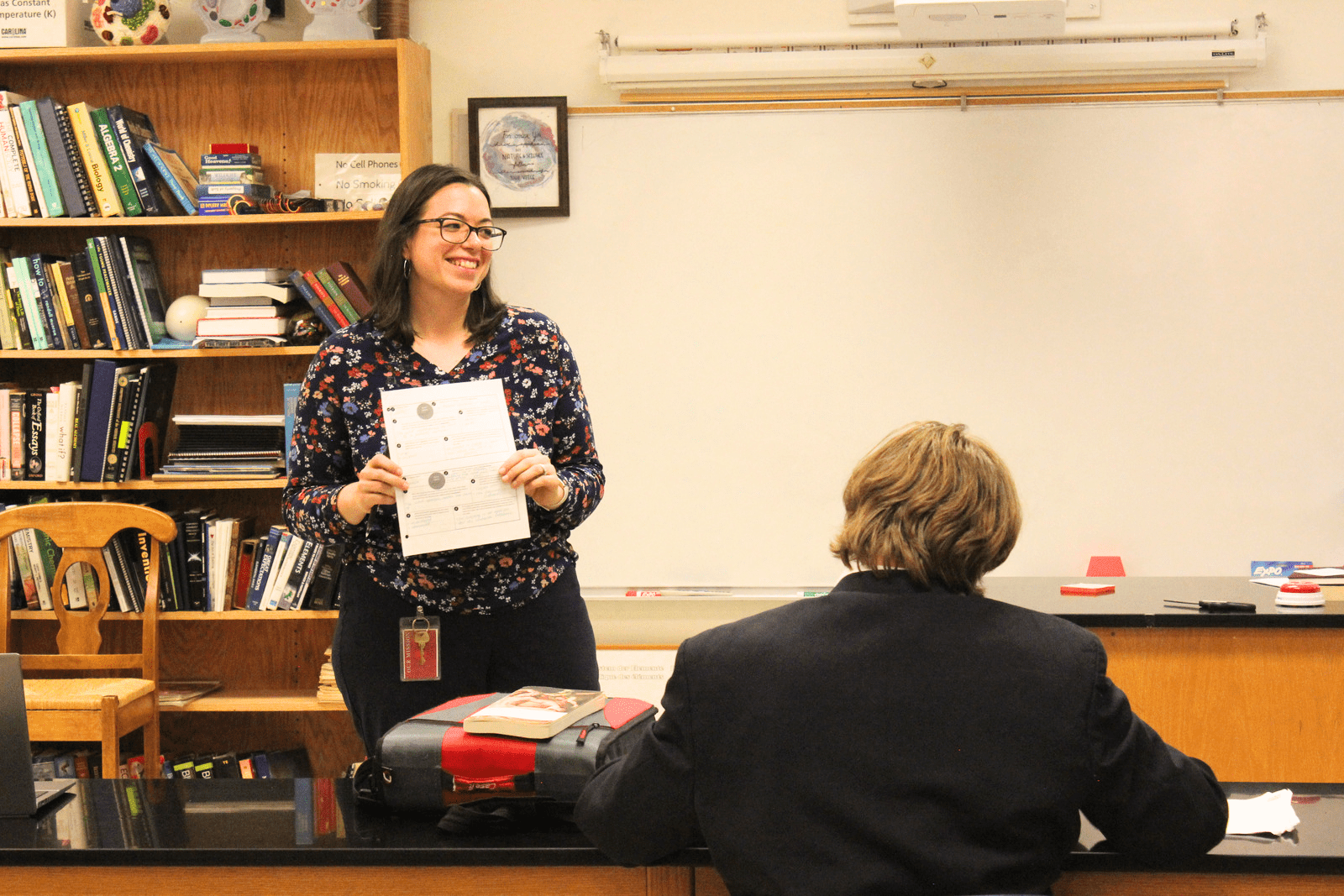

Rhetoric is, of course, the art of writing and speaking, but it is much more than that. As Aristotle taught us, the largest part of rhetoric is “invention,” which is the skill of discovering and employing arguments to the topic at hand.

The classical curriculum is coherent because every discipline can be taught grammatically, dialectically, and rhetorically. In practice even a young student can operate in all three modes, and the advanced student is successful when he can use these tools of thought simultaneously.

Second, the classical, Christian curriculum is coherent because it recognizes that each course of study is not a mere collection of facts to be learned; rather, each discipline rests on universals within the human experience, what we call “great questions.” These questions are central to a classical, Christian curriculum, and they shape the contours of the educational landscape. (Some of these questions are in the margins of this newsletter). Reaching these questions is central to the program. Knowledge of these questions, and how they have been answered within the Christian tradition, is the very definition of what it is to be classically educated.

To cite but one example: On a first reading of Homer’s Odyssey, the student realizes that he is encountering a wild tale about a man who survives dramatic dangers as he tries to return home from war. While it’s engaging enough on that level, a closer reading reveals a man who is a rightful ruler, but is stuck on an island, longing for home, pining for his wife and countrymen. We learn that the soldier who left for battle a decade before must be transformed in his character before he would rule other men. It is a story about human identity, what it means to belong to a people, and what is required for one’s transformation.

Boiled down, the great questions in this story include: What is man? How is he saved? What is love? What is courage? How does man relate to the divine? In a Christian context, we could transform this further: How does a man obtain the divine image? These are but a few “great questions” Homer raises.

When these questions come into view, the student is finally in contact with the goal of the classical, Christian curriculum. He is entering into a potentially transformative experience. The literature course is not simply about knowing the facts of Odysseus’ journey. The course is concerned with the deeper and personal question, “Who are You?”

The classical, Christian curriculum introduces a student to the great conversation about enduring human questions. This conversation begins early. Every third grader at New Covenant learns his ancient Greek and Egyptian mythology right alongside his Bible studies and math facts. Piece by piece, block by block, the student is prepared for serious study as a young adult in high school.

This is the distinguishing feature of New Covenant Schools. Because life’s great questions are of the highest concern, and because they are value-laden, and often inherently religious, a secular or progressive curriculum cannot organize around them or engage fully with them. Thus, it is no surprise that the classics have been abandoned or worse, deconstructed.

The New Covenant curriculum is built on the classical, Christian tradition, and achieves coherence both in method and content.