“Show me what reverence looks like.” Lately I’ve been saying this at the beginning of each of my middle school chapels. The children aren’t being bad; they’re coming from gym, lunch or some other class. They’re jousting with their friends, being noisy, sometimes to the point of rowdiness. It’s hard to get them seated; it’s harder to move them to a frame of mind for something like…chapel.

I continue with an enforced silence often lasting more than a minute. It always feels longer. I make the children be quiet. I make them stop talking. I make them stop wiggling. I make them stop looking at their neighbor from the corner of their eyes. Most of the time, after about forty five seconds, it begins to get a little uncomfortable. Few of our youngsters are ever silent for that long unless occupied with a movie or TV show. Imposing silence is something I do to create space between the last thing the students were doing before moving to the thing they are about to do. That distance – that space – is necessary for teaching the sensibility of reverence.

Reverence doesn’t come naturally to Americans. Since before the founding of the Republic, suspicion of power and authority – and ultimately revolution – have been part of our national DNA. Honor, when it is given, is offered to those who earn it. It is often withheld from others to whom it might be due, who, by position or title, should be honored.

Reverence is an attitude that blends fear and honor. This is not the kind of fear that instills panic or causes pain. It’s not the urge to run away. It is better understood as a sensibility that forbids obtrusiveness, that causes one to keep a distance from the object that is revered. In his book, Learning the Virtues That Lead You to God, Romano Guardini reminds us that “in reverence man refrains from doing what he usually likes to do, which is to take possession of and use something for his own purposes. Instead, he steps back and keeps his distance. This creates a spiritual space in which that which deserves reverence can stand erect, detached, and free, in all its splendor. The more lofty an object, the more the feeling of value which it awakens is bound up with this keeping one’s distance.”

Reverence is something we cultivate chiefly for God, but we also cultivate it for other people, for great works and for nature itself. In its everyday form reverence flies under another name: respect. When students are taught to respect their teachers and one another, they demonstrate a desire for the privacy of another person. They realize that they are not entitled to know everything about a teacher’s private life, and the same is true for the student. The good teacher enforces those boundaries, boundaries that create space so that their gifts, standing fully erect and free, are perceived by the student for what they are. students who respect one another’s private worlds come to value others not for what they have, but simply for who they are. In the hallway, this is expressed with simple courtesy. Manners, after all, are morals writ small.

The idea of privacy is at the heart of respect, and it is increasingly difficult to teach because we live in a world of no secrets. TV shows are based upon the exploitation of the private worlds of hurting people, served up as entertainment. When we are not peering into the secrets of someone on a reality show, we can occupy ourselves divulging ourselves on social media, shrinking what is left of our own private spaces, exhausting what should be held in reserve.

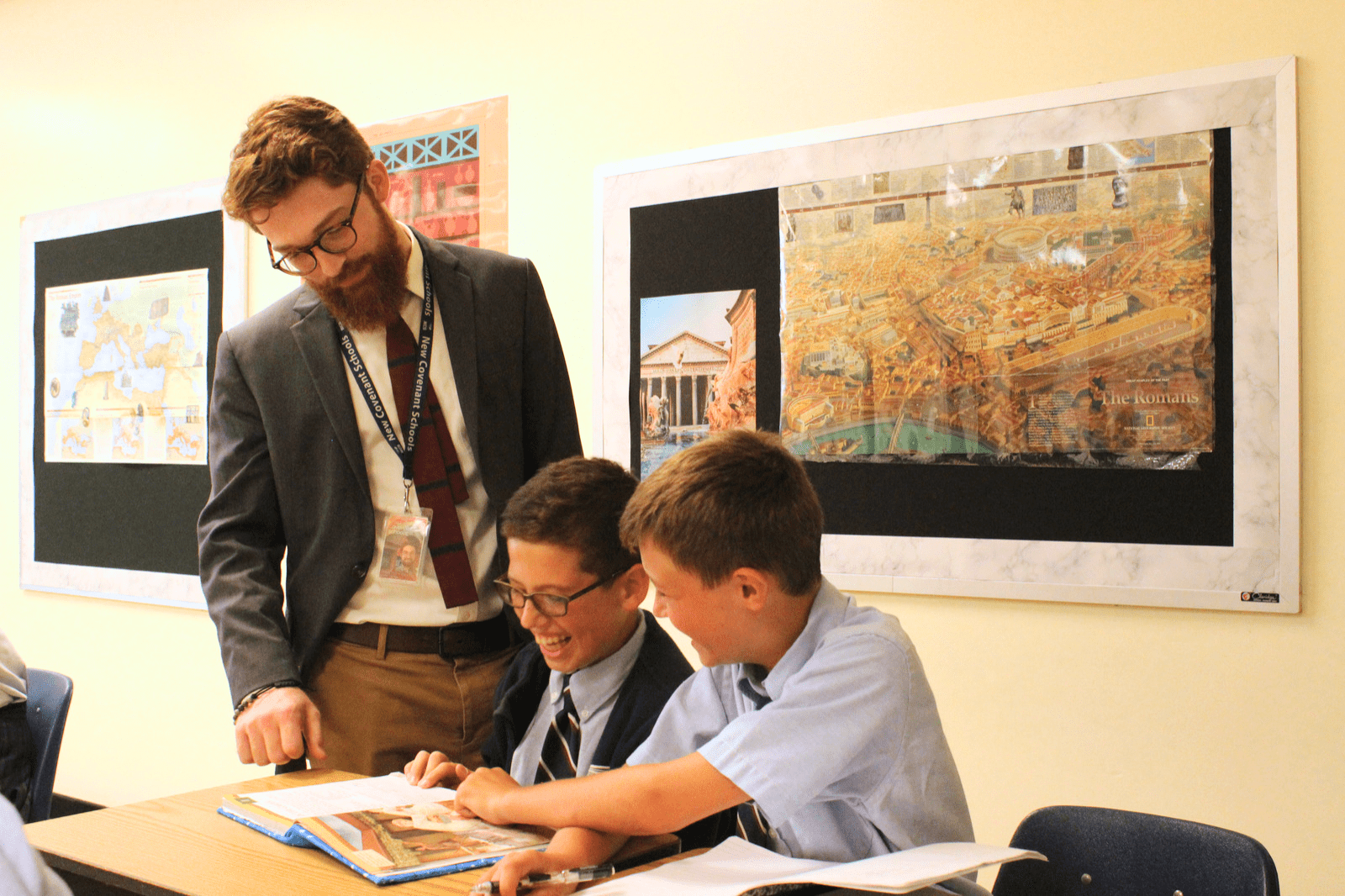

In the end our children are powerfully shaped by a world devoid of reverence. The space once occupied by awe, honor, and a fear of trespassing, is so lacking that students have trouble coming to terms with reverencing something like an ancient text. Day in and day out, however, we place students in the presence of greatness: great books, great ideas, great stories, and great wonders of nature. Our hope is that they may respond to their education with a heartfelt reverence for the religious and cultural heritage that belongs to them.